It’s been an interesting phenomenon to watch so many educators flock around Daniel Pink’s best-selling book, A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future. The book is a rallying cry for more creativity and arts, especially in K-12 education. It’s hard to argue with that. Stories of schools canceling recess, arts, music, even history and science to focus on boosting math and reading test scores makes your heart hurt. It’s beyond tragic to know in your bones that we are boring kids, wasting their time prepping for tests that don’t matter, and ultimately losing them.

It’s been an interesting phenomenon to watch so many educators flock around Daniel Pink’s best-selling book, A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future. The book is a rallying cry for more creativity and arts, especially in K-12 education. It’s hard to argue with that. Stories of schools canceling recess, arts, music, even history and science to focus on boosting math and reading test scores makes your heart hurt. It’s beyond tragic to know in your bones that we are boring kids, wasting their time prepping for tests that don’t matter, and ultimately losing them.

It’s a gift to be able to raise a bestselling book like a golden shield against this insanity. Right?

But what if this gift is actually fool’s gold. What if it’s a misleading accumulation of misinterpreted anecdotes, pseudoscience, made up “exercises” and a profound misunderstanding of math, engineering, and science. Does this help or hurt educators who are trying to improve schools? Can you build a solid case for change on a foundation of sand?

Plus, I think Daniel Pink hates me.

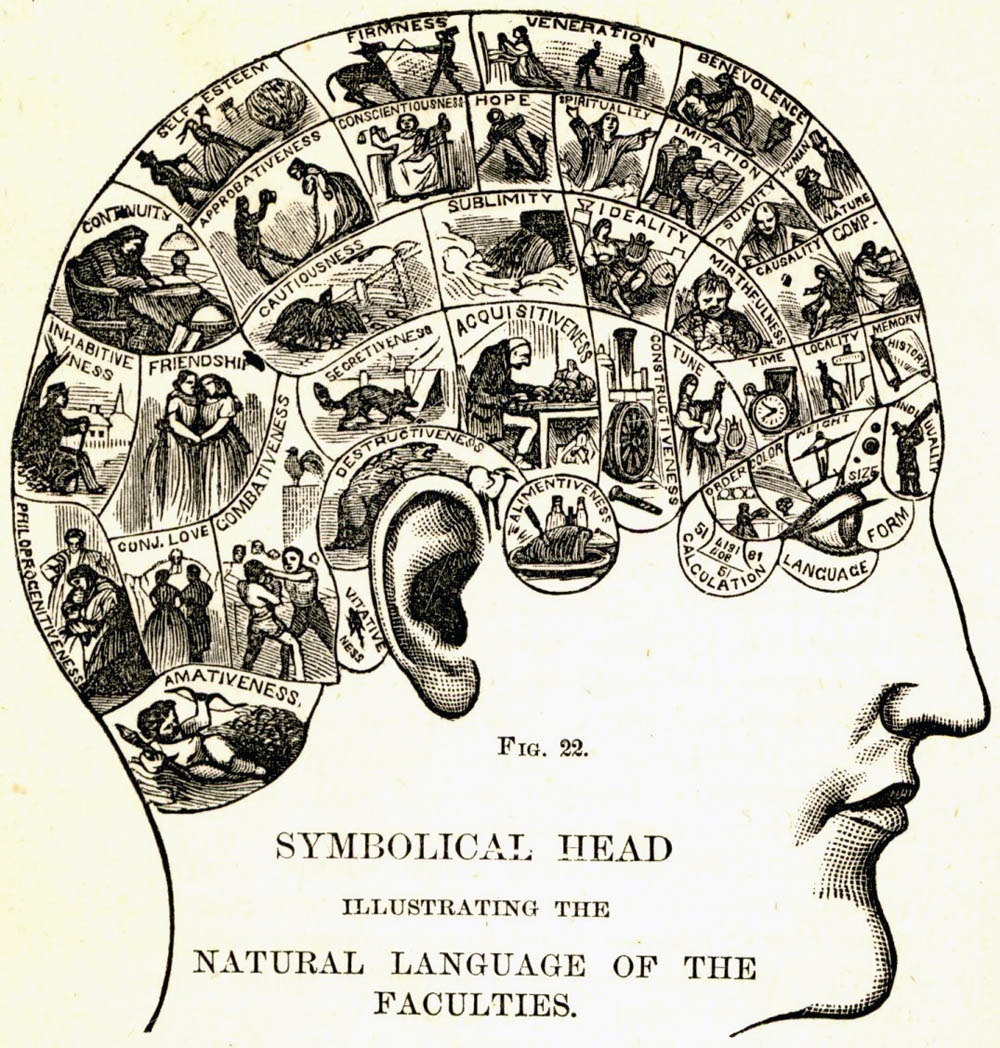

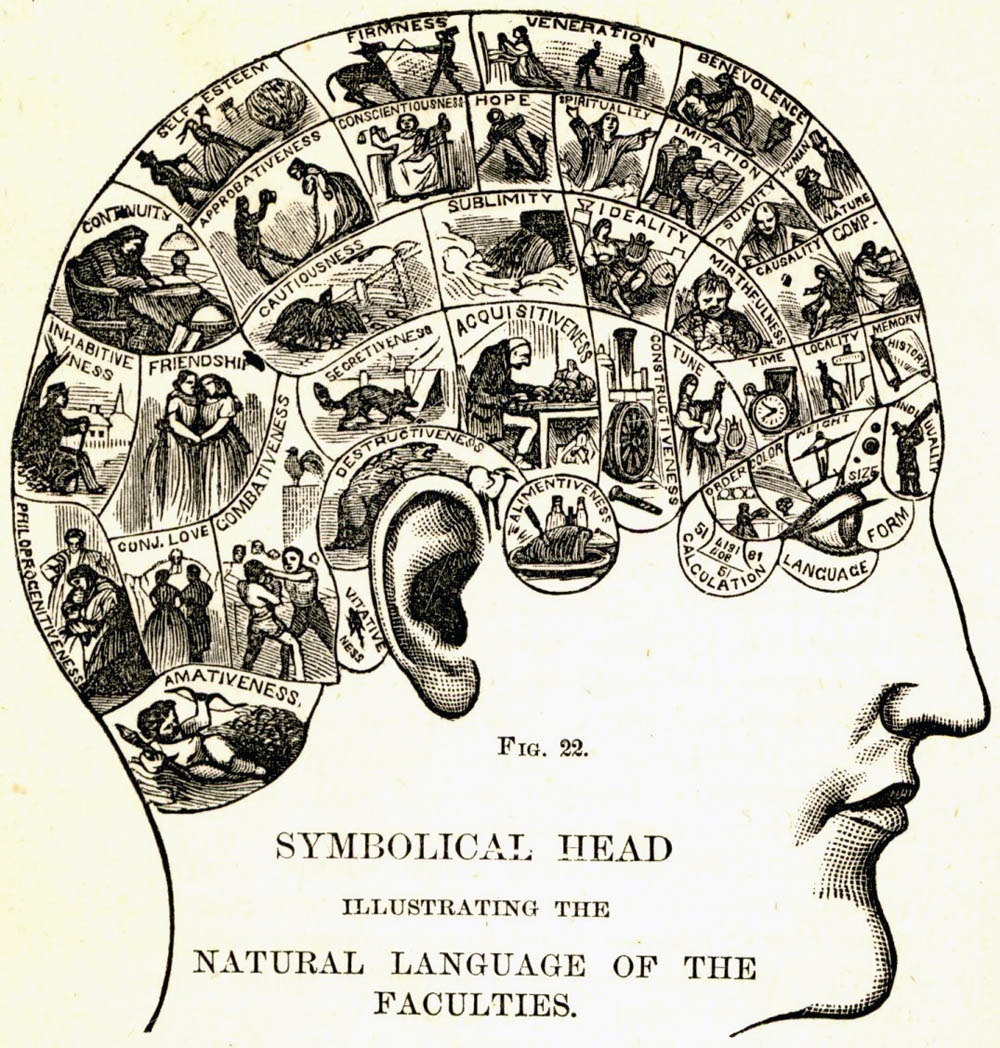

Pink describes so called left-brain characteristics as “sequential, literal, functional, textual, and analytic” and assigns them to programmers, accountants, and people who got good grades in school. According to Pink, these attributes are “…prized by hardheaded organizations, and emphasized in schools.” This is in contrast to right-brain people who are “creators and caregivers, shortchanged by organizations, and neglected in schools.”

I’m a woman who loves math and science, earned an electrical engineering degree and worked as a programmer in the aerospace industry. Obviously I fall into the “left brain” camp. But although I got pretty good grades in school, it was spotty. I did great in Algebra and Physics. I was terrible at Geometry and Chemistry. I have no idea why. Maybe I was only “left-brained” in even years.

As I read Pink further, I became more and more puzzled. Right brainers are the future, the key to staying globally competitive. They are more caring and probably better looking. What did I do to deserve this life sentence of obsolescence? Where does all this animosity towards me and my kind come from? And shouldn’t I be making more money from some “hardheaded organization”?

It’s incredibly divisive to create two types of people and set them up in competition for grades and good jobs. It’s also ludicrous and misleading. You might as well say that all artists have emotional problems or all musicians have long hair. It plays into silly cliches and jealousy (or fear) of people who aren’t like you.

There are many types of people who happen to be good at math, science, or programming. Some are good at the school version of these subjects and some aren’t. To draw a hard line between the sciences and creativity shows a profound misunderstanding of both. I can tell you that programming is as close to composing music as anything else. It’s something that you feel, that you can lose yourself in, that comes from a place inside that is sometimes unexplainable.

I guarantee you that programmers out there are going, “w00t! tell it sister!” - and everyone else is thinking, “are you kidding?” But you have to believe me. Math, science, programming, and engineering are deeply beautiful and creative. Look — I believe you when you tell me that opera soothes your soul or that paint poured on a basketball is art. (I don’t really, but I’m polite enough to take your word for it. So take my word for this, OK?)

It’s a shame that this beauty is often lost in the K-12 curriculum. But that’s a problem with curriculum, not a problem with people’s brains.

Building his case on such an impoverished view of creativity in the sciences weakens everything Pink says. It shows a profound misunderstanding of people who aren’t like him and sloppy thinking about the cause and effect relationships he claims exist.

I’m suspicious of his analysis especially where it relates to children and learning. Pink tells a story about an artist visiting a school. He asks each classroom full of children if they are artists. In the kindergarten class, all hands go up with enthusiasm. In the first grade class, fewer hands go up, and so on, until by the sixth grade no hands go up. He concludes that the world doesn’t value creativity.

Oh, please. If you ask kindergartners if they want to be scientists, ballerinas, firemen, astronauts, or pretty much anything, you will get an enthusiastic show of hands. Sixth graders won’t. It has nothing to do with the value of art and everything to do with understanding the difference between 5 year olds and 13 year olds.

In another vignette, he takes us to a charter school for architecture and design, where students work on real world, interdisciplinary projects. He reveals that this school is safe and orderly, colorful murals line the halls, it has no metal detectors, and attendance is high. According to Pink, the success of this school is due to the “design” focus of the curriculum. However, anyone with any sense can see that creating a caring school with a relevant curriculum is the reason for its success. But apparently, looking at facts is simply old-fashioned “left brain” (hiss, boo) thinking.

Pink has no qualms about using anecdotes like this that not only don’t support his conclusions, but stand in direct contrast to what he is saying. Luckily for him, he is an accomplished writer. I stand in awe of his ability to enthusiastically plunge past inconsistencies on his way to trumpet unsupported conclusions.

I’m all for encouraging creativity in schools, but treating A Whole New Mind as a blueprint seems rash and insubstantial. This book celebrates fake science and entrenched stereotypes about people that are harmful and hurtful. Schools need to celebrate the gifts of all children, not label them as “new” or “old”.

Besides, he hates me.

Sylvia

It’s been an interesting phenomenon to watch so many educators flock around Daniel Pink’s best-selling book, A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future. The book is a rallying cry for more creativity and arts, especially in K-12 education. It’s hard to argue with that. Stories of schools canceling recess, arts, music, even history and science to focus on boosting math and reading test scores makes your heart hurt. It’s beyond tragic to know in your bones that we are boring kids, wasting their time prepping for tests that don’t matter, and ultimately losing them.

It’s been an interesting phenomenon to watch so many educators flock around Daniel Pink’s best-selling book, A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future. The book is a rallying cry for more creativity and arts, especially in K-12 education. It’s hard to argue with that. Stories of schools canceling recess, arts, music, even history and science to focus on boosting math and reading test scores makes your heart hurt. It’s beyond tragic to know in your bones that we are boring kids, wasting their time prepping for tests that don’t matter, and ultimately losing them. No longer will you have to rely on Shirley McLaine to find out that you have an Egyptian princess or a Russian nobleman in your past. You can find out for sure and maybe they’ll come pay you a visit. 6 degrees of separation? No longer is it just a party game ending in

No longer will you have to rely on Shirley McLaine to find out that you have an Egyptian princess or a Russian nobleman in your past. You can find out for sure and maybe they’ll come pay you a visit. 6 degrees of separation? No longer is it just a party game ending in  The process begins, disgustingly enough, with spit. You purchase a $999 “spit kit” and you supply the requisite DNA. The company,

The process begins, disgustingly enough, with spit. You purchase a $999 “spit kit” and you supply the requisite DNA. The company,  I have been tagged by Rick Weinberg (

I have been tagged by Rick Weinberg (